Since the Information Age, the proliferation of the written word[1] and bibliophilia[2] have largely become a veil to modern understanding of the ancients. For instance, it may surprise many readers to note how many times the Biblical books reference oral teaching, those which are spoken and heard, not just read and written. In other words, what doctrines the biblical authors held as divine were not just ink on papyrus or parchment, but were living words spoken by men and women of God. There is a great commission to the disciples to teach the gospel and to confess Jesus with their mouths, not to distribute scrolls to every hotel nightstand. Even on the one occasion when Paul asks that his letters be distributed to other congregations, he asks that they be read to the congregation; he even cut at least one letter short and said that he would save some of his message for telling them in person.[3] There are many references to prophets delivering such divine messages, but the emphasis for correct doctrine is quite often placed on the apostles’ teachings.

This article is from my book, When Humans Wrote Scripture.

In fact, there are several passages in the New Testament that show the paramount importance of the teachings of the apostles, and that their teachings were tantamount to those of Jesus, and therefore had divine authority. Apostles are listed as first in Paul’s list of spiritual gifts. In the beginning of the church history in Acts, it was the apostles’ teaching that they were said to have continued in, and the apostle’s signs and wonders that convinced people. It was they who had the leadership, receiving and distributing offerings. The apostles would go to certain congregations, lay their hands on some, and they would “receive the Holy Spirit”. When councils were called in Jerusalem, it was “the apostles and the elders” who decided such questions, and their edicts that went out to the congregations abroad. The church itself was said to be laid on the foundation of the prophets and apostles, with Jesus being the cornerstone, the apostle and high priest of the confession.[4] In other words, the apostle’s teachings were not just from Jesus, they were the very essence of all Christian doctrine.

Many New Testament books appeal to apostolic authority to bolster the work as authoritative.[5] However, the next question that arises then, if the apostles are the source of authoritative teachings, is who were these apostles? Most everyone who’s been to Sunday school probably thinks they know the answer to that question, but by the end of this section, my bet is most readers will see a lot more information on the topic that is not taught in most Sunday schools, at least not in Protestant churches.

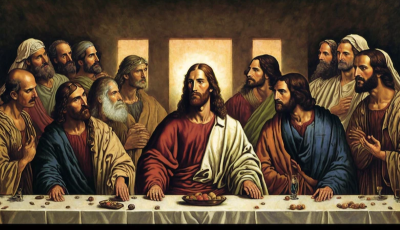

The Twelve?

Most Christians’ first thought would probably be to define the apostles as the twelve that Jesus chose (with Judas, the traitor replaced by Matthias, of course[6]). In fact, the gospels and beginning of Acts often speaks of “the Twelve”, as they figure prominently in the narratives, at least as a group. Or do they? Let’s focus on them first.

Who were these Twelve? Firstly, we’re given differing lists, and many modern scholars view these differences as evidence that the gospels were written so long after Jesus that the oral traditions were no longer reliable regarding even the names of the twelve.[7] However, most of those differences seem to have a simpler explanation. John mentions a Nathanael that the other gospels and Acts do not; could he be Bartholomew, which means “son of Tomai”? Some scholars think so; interestingly, Richard Bauckham[8] does not think that these two are the same person, since he thinks it unlikely that someone would feel the need to replace one less common name with another; and yet Bauckham, ironically, has no issue with harmonizing Thaddaeus (listed in Matthew and Mark) with Judas the son of James (only found in Luke, John, and Acts),[9] since it was not uncommon for Jews to go by both a Greek and a Semitic name.

| Matt 10 | Mark 3 | Luke 6 | John | Acts 1 |

| Simon/Peter | Simon/Peter | Simon/Peter | Simon/Peter/Cephas | Peter |

| Andrew (Peter’s brother) | Andrew | Andrew (Peter’s brother) | Andrew (Peter’s brother) | Andrew |

| James (“son of Zebedee”) | James (“son of Zebedee”) | James | one of the “sons of Zebedee” | James |

| John (James’ brother) | John (James’ brother) | John | one of the “sons of Zebedee” | John |

| Bartholomew | Bartholomew | Bartholomew | Nathanael | Bartholomew |

| Thomas | Thomas | Thomas | Thomas (Didymus) | Thomas |

| Matthew (the tax collector) | Matthew | Matthew | N/A | Matthew |

| James (son of Alphaeus) | James (son of Alphaeus) | James (son of Alphaeus) | N/A | James (son of Alphaeus) |

| Thaddaeus | Thaddaeus | Judas (son of James) | Judas (not Iscariot) | Judas (son of James) |

| Simon (the Canaanite) | Simon (the Cananaean) | Simon (the Zealot) | N/A | Simon (the Zealot) |

| Judas Iscariot | Judas Iscariot | Judas Iscariot | Judas (Son of Simon Iscariot) | Judas who killed himself |

But apart from the difficulty in even nailing down the name of at least one or two of the twelve apostles, or whether Matthew being Levi was an invention of Matthew, the next question that arises is, if they were to bear witness of the teachings of Jesus, why do we not hear another word about several of them, much less have works written by them? In fact, the apostle lists are the only place some of the twelve apostles are even mentioned. If they were to bear witness to Christ and his teaching, where is their witness? Of course, a huge percentage of modern Christians have an answer to that: at least part is found in the works of the earliest patristic writers. We’ll not go down that trail here though.

How many of the twelve apostles had New Testament content claimed to be written in their name? Seriously, think of the answer before reading further. Most scholars would say that the answer is one, but I’m going to argue it’s two. The book of Revelation claims to be written by a man named John,[10] and two letters of Peter. Yes, that is it. There is actually no explicit claim of authorship for any of the gospels, which have the appearance of being written anonymously.[11] There are early traditions that Matthew and John were written by those apostles, which most scholars doubt; however, in a later book I intend to point out several evidences to the contrary that scholars overlook. Mark and Luke are mentioned in Acts as companions of the apostles, but not apostles. An often missed detail is that the two books attributed to Luke are longer than the combined writings attributed to any other author of the New Testament; those two books have greatly influenced what Christianity became; we’ll see below the significance of this, relative to his sources of information, which he says he got, not from God, but from another source!

The Thirteenth Warrior

You seldom hear mentioned in Bible classes that Paul, who never met Jesus before his crucifixion, much less accompanied them from the baptism of John until the ascension,[12] came along and claimed apostleship, or that much of his letters are devoted to defending his apostleship. In fact, the legitimacy of Paul’s apostleship seemed to be no small issue for him, judging by the amount of space he devotes to defending it. Such lengthy defenses, one would imagine, could only be the result of a significant number who rejected him. But as we’ll see, that would not last, because Paul would go on to be one of the most influential writers of the New Testament, if not the most. So now we’re no longer discussing “the Twelve”, but “the Thirteen”.

Paul often emphasizes that he is speaking with divine authority, even that his message should be used to test others who claim to have a prophecy.[13] He ordered on a few occasions that his letters be read before the congregation. He argues that he was an apostle to the Gentiles, whereas the Twelve (or at least Peter)[14] were the apostles to Israel: in the chapters that follow, we will see if his Christianity matched theirs, as Acts seems to try to prove, or whether it was in truth quite different.

So we’ve seen that there were thirteen apostles. But wait, there’s more!

Other Apostles?

I was raised in the so-called Bible Belt of the United States, possibly the most religious Christian population in the developed world, and it is predominantly Protestant, and mostly evangelical and fundamentalist-leaning. I have firsthand experience of hearing teachings for over four decades now on the apostles. Every teaching I can remember in such settings only recognized the twelve apostles, and Paul. Almost never is it mentioned that Paul was not one of the twelve. Apostolic succession is almost never mentioned, and my experience is that it is categorically denied when it is. The first chapter of Acts is often cited as an example of an appointment of an apostle, and it’s noted that his qualification was that he had been with Jesus for the bulk of his ministry; the narrative that I heard growing up was that this precluded the appointment of more apostles after that generation of witnesses had passed away. Never mind that Paul did not meet that qualification.

The funny thing about this view of who were considered apostles, which is supposedly based on Scripture, is that it ignores multiple passages that show conclusively that the Biblical authors believe there were other apostles. Several others.

Paul cites the “brothers” of Jesus as apostles,[15] which is most likely at a minimum a reference to both James and Jude, who were almost certainly not one of the Twelve.[16] There’s even an excellent argument for the preeminence of James, the brother of Jesus, among the apostles, which I will make elsewhere, based on Paul’s own writings. So here we likely have two extra apostles on top of the 13. Were there more?

In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul makes perhaps the most compelling statement regarding additional apostles. He is recounting the order in which Jesus appeared to people. He appears to give two groups of three. In the first group, which only partially agrees with the gospels,[17] he mentions Peter (aka., Cephas), giving him preeminence just as the gospels and the first 12 chapters of Acts do; then he mentions the Twelve, and 500 brothers at once. In the second group, he lists James as preeminent, then “all the apostles”, then himself, as the “least of the apostles”. Note that “the apostles” are listed as a separate group from the Twelve and James! Paul confirms that there were in fact a plurality of apostles apart from the Twelve, himself, and James the brother of Jesus!

But wait, there are even more specific mentions of individuals. Barnabas is also called an apostle in Acts 14:14. Romans 16:7 may refer to Andronicus and Junia (a woman) as apostles, depending on the translation, for the Greek is actually ambiguous here: it basically states that they are known among the apostles; the interpretation depends on who is doing the knowing; some have argued that Paul was giving his testimony that they were (known) apostles based on the context, for why would he just say that the apostles knew them? Silvanus and Timothy may have been considered apostles, too, assuming the author of 1 Thessalonians did not switch “we” between 1:1 and 2:6. There’s a similar case for arguing that Apollos was also an apostle based on 1 Corinthians 4:6-9, as well as other mentions of him in the letter. Most translations call Epaphroditus a “messenger” in Philippians 2:25, but the same Greek word for apostle is used. And in 2 Corinthians 8:16-23, we find two individuals who curiously go unnamed; they too are called messengers/apostles. We’re up to a couple of dozen now, if anyone is counting.

By this rationale, Titus, who appeared to have similar standing with Timothy, could have been an apostle. For Mark and Luke to have authority to write (if they indeed wrote) could mean that they actually had standing as apostles, as some of the patristic writers believed. We simply do not know if they were considered apostles in their own time.

It is not my purpose to debate whether there was an apostolic succession, much less whether there was a legitimate one ordained by a god. However, many of the earliest patristic writers testify that there was in fact such a succession, and more than half of all Christendom today belong to denominations that teach that there was one, and even some Protestants I’ve encountered believe it.[18] In other words, some form of apostolic succession is a majority view in Christendom even to this day.

Why might it matter whether there was some sort of apostolic succession, or at least a plurality of apostles in the early days? Because the New Testament places such tremendous importance on their teaching, as the foundational doctrine of Christianity, in fact. Although the authors spoke sometimes against the “traditions of men”,[19] the traditions of the apostles was God’s very command, some would even argue a pattern for the church.[20] By this expanded list of apostles, we see the authority of such books as James and Jude as established. By apostolic teaching and guidance, many believe that the apostles’ companions Luke and Mark received their information. And finally what might be the most pertinent question of all, a critique of a doctrine of some Protestants, that only written Scripture can provide revelation:[21] how can one accept the teaching of the Bible as the only source of authority, yet reject the teachings of the ones who gave the canon? Even the canon itself, it has been argued, is a tradition delivered down to Christianity, especially since there is no canon list inside of Scripture.

If one were to ask a large sample of Christians to explain how they know the books in the Bible are from God, one is likely to get many different answers, and also a great many “I don’t knows”. For the canon is in fact a tradition, whether preserved by God, apostles, or councils of men. And, although the denominations have established creeds for how they interpret each book of the Bible, none that I know of have systematically explained why they are Scripture. If one were to try to do so, problems would arise, problems of different voices and understandings of even the nature of Christianity, as well as differences in how one is to act like a good Christian; the reason why these issues do not currently arise in most churches, in my experience, is because the books of the Bible are treated as a unity, and their doctrines amalgamated and harmonized. If a biblical teaching or detail doesn’t fit a prevailing belief, it is glossed over. Yet if you do not look at them this way, you find all sorts of contradiction. These are matters to be examined throughout the rest of this book. It may sound like I am arguing against inspiration, but bear with me. Even the most fundamentalist believers admit some contradictions, even if they think there are reasonable explanations for them, such as how one law prohibits pork, and another permits it. But our view of the development of Scripture and its doctrines will go far beyond the typical Protestant Sunday school’s examination regarding whether the Bible speaks of God giving new dispensations. We’ll even consider how modern ideas of law itself are often quite different than those of the biblical authors.

Human Sources?

The Bible has a few plays on non-biblical quotes, such as when Titus 1:12-14 says that all Cretans are liars, a reference to Epimenides’ paradox (ca. 600BCE), but this does not appear to be a serious appeal to a source for divine revelation. So does the Bible actually cite extra-biblical sources which are not now considered inspired, as authoritative? In later chapters, we’ll cover the multiple sources of the Hebrew Bible that we no longer have. Some of them were prophets. However, some were probably secular, such as the official chronicles of kings. This is not a dropped-from the sky paradigm of inspiration.

Nor is it for a biblical writer to get his message, not directly from God, but from other people. There is very strong evidence that both Matthew and Luke copied much from Mark, as they often match verbatim, and not just quotes that Jesus said. Their narrative accounts often match word-for-word, to the extent that moderns would call it plagiarism.[22]

Some fundamentalists would probably have no problem with Matthew and Luke getting significant content from Mark, since they probably consider Mark’s work inspired. (Let’s hypothesize for a moment a common fundamentalist perspective, that the gospels were written by the men who were ultimately attributed to each.) But circular reasoning should be avoided. Recall that Matthew was supposed to be the apostle, one of the foundation stones of the doctrines of Christianity. It does not seem logical to conclude that Mark was accurate because he got his information from apostles, if an apostle is copying him. Of course, it’s conceivable that God just wanted Matthew to copy Mark for some undisclosed reason…. Or that Mark was also an apostle, as examined above.

But the biggest surprise to fundamentalists may not be that a book supposedly written by the apostle Matthew was copied from a (possible) non-apostle. The bigger surprise should be that Luke baldly admits that his accounts come, not from God, but from other people.[23] Many believers have argued that Luke’s sources were apostles, which might be implied by the accounts of his journeys with them in the second half of Acts. However, he never explicitly states the apostles as his source. In fact, “those who were from the beginning eyewitnesses” could refer to anyone who saw the acts and teachings of Jesus while he was alive. Is this even a claim to inspiration? Is it just the ancient version of proof of good journalism?

Almost Three Centuries Before Nicaea

And while we’re on the topic of sources, we should note one more curious detail, from Acts 15, in which we find a council called to answer the question of whether gentiles needed to be circumcised. The elders and apostles at Jerusalem gathered to decide the question. Yet we’re told that apostles as well as other individuals with the gift of prophecy had a direct line to God’s will. Why would they need a council to decide the question? More significantly, why was there “much debate” among them about it? Why did they have to resort to trying to dig the answer from existing revelation that did not explicitly address the issue? Why did the apostles, who we’re told had God’s special revelation, not unanimously say “this is what God says”? Note too the reliance on men of renown. I also believe the order in which they speak is significance.

First, Peter reiterates what he learned in chapter 10 by special revelation: that the Gentiles were also accepted. It’s curious that this detail had not been revealed earlier, also.[24] Secondly, Paul supports the premise of the acceptance of the Gentiles by testifying of the miraculous signs worked among them.

Then the third argument comes from James, who I will argue elsewhere is the brother of Jesus and quite probably chief among the apostles; here I will suggest that his last word is the weightiest to the author of Acts. James quotes from the Hebrew Bible in order to prove the point that Gentiles need not be circumcised. However, from the perspective of us moderns, James does not quote a passage found anywhere in the Hebrew Bible; that would not have been an issue for readers of Acts, for he seems to be amalgamating three passages: Amos 9:11-12, Jeremiah 12:15, and Isaiah 45:21. However, even if you consult these passages in your Bible, they still do not say exactly what James states. Firstly, this is because he appears to be using the Septuagint; secondly, he is doing some paraphrasing of his own. For instance, instead of “Edom” in Amos 9:12, James inserts a very interpretive “remnant of mankind”. But James’ gist, that Gentiles were prophesied to worship with Israel, is indeed found in the Hebrew Bible.

But note that all three of these presentations tend to prove one point: that God would accept Gentiles to worship him. None of them actually directly deal with the issue of whether those Gentiles must keep the whole law of Moses. Maybe it was assumed and understood that the comment of Moses in Deuteronomy 5:3, that YHVH only made the Mosaic covenant with Israel, was a foundational principle, and that the only thing left to settle was whether God accepted the Gentiles among his chosen people who worship him. This, however, flies in the face of a long-standing practice of foreign proselytes keeping the law of Moses! And why they did not cite Jesus, whom Luke, which seems to be portrayed as written before Acts, clearly presents as teaching that his revelation of the gospel was also for the Gentiles?[25] This Jerusalem council is taking place years after the death of Christ. And why would they have gone so long without knowing that their mission was not to all the world and not just the Jews, a tiny percentage of the world population?[26]

But perhaps the most pertinent question that’s raised by James’ appeal to the Hebrew Scripture is why he ignores much more explicit passages that show that Gentiles would in fact worship YHVH. And perhaps the reason he did not quote at least some of them is quite possibly because they prove exactly the opposite of what the council decided: that Gentiles were in fact prophesied to follow the law of Moses when the kingdom of God was finally established under the quintessential Davidic Messiah.[27]

Interestingly, the council does in fact lay down four laws for the gentiles which are found in the Law of Moses: that they should abstain from things polluted by idols and sexual immorality, and from anything strangled and from blood. But James does not say “God revealed this to me”; he simply states “Therefore, I have reached the decision….” Was this that “binding” and “loosing” that Jesus authorized Peter (and the other apostles?) to do in Matthew 16 when he gave them the keys to the kingdom? As we will see in the latter chapters of this book, at least one of these laws would also be contradicted by at least one major New Testament author. But the point that I want to emphasize here is that at no point does the council appeal to special revelation, but only to the judgement of these men based on the less explicit, special revelation that they already had. I would submit that this is perfectly inline with the views of the law evinced in the books of Moses, in which we see some of the laws of the Torah being modified even in the time of Moses (see chapter 4). But the main point I want to make here is that the doctrines presented in such passages as Acts 15 are not being portrayed as special revelation: not a dropped-from the sky paradigm of inspiration. Not even “verbal plenary”.

[1] See the section below on extra content.

[2] Meaning the love of books in general, not just the Bible. There is an excellent argument that this bibliophilia and the reliance on the written word that pervades even our own culture to this day is an inheritance that can be traced back to the oppressed Hebrews of a tiny strip of land between three continents, Canaan.

[3] Colossians 4:16; 1 Corinthians 11:34

[4] 2 Peter 3:2; I Corinthians 12:28; Acts 2:42; 4:35; 15; 16:4; Ephesians 2:20; Hebrews 3:1

[5] E.g., I John 4:6. There are also likely implied apostolic authority, such as Luke’s accounts of his time with the apostles, or the accounts of apostles within the documents delivering certain teachings, such as in Acts, even when there is no claim to apostolic authorship of the book or letter.

[6] Acts 1:21-26

[7] See for example The Gospel According to Luke I-IX, by J. A. Fitzmyer, p.620.

[8] In Jesus and The Eyewitnesses, chapter 5 “The Twelve”.

[9] When I say that Bauckham “harmonizes”, I mean that from a logical perspective; he is certainly not a fundamentalist apologist, despite his arguments that the gospels contain much eyewitness testimony: for example, he holds that the book of Matthew was not written by him, and that the profession of “tax collector” was an interpolation added in Matthew, as Mark and Luke do not mention this profession, and give the name of Levi for a tax collector who was discipled. Compare Mark 2:13, 14 and Luke 5:27-29 to Matthew 9:9; 10:3.

[10] Some scholars have pointed out the author does not specify which John; Dale Martin even claims that it was a different John; however, it seems likely that it is understood to be the John of apostle fame, even—and especially—if Revelation is pseudonymous.

[11] I would argue that the author of the gospel of John actually intended to imply his authorship, but will not go into it here.

[12] This appeared to be one of the criteria for selecting Judas’ replacement in Acts 1.

[13] I Corinthians 14:37, 38

[14] Galatians 2:7

[15] 1 Corinthians 9:5. Mark 6:3 gives the names of Jesus’ four brothers, and mentions an unknown number of unnamed sisters. There is an argument put forth by Richard Carrier that Paul is not necessarily referring to the fleshly brothers of Jesus because elsewhere he argues that all believers are siblings of Christ; I submit this is the sort of eisegesis typically performed by Christians that want to find what they want in Scripture.

[16] Acts 12, particularly, mentions the death of James the son of Zebedee, then mentions another James. One may occasionally find an argument that the Judas of the Twelve who was not Iscariot was actually the brother of James, not the son of, which is how it’s rendered in a few translations, and is actually a possible interpretation of the Greek, not a variant; but Judas of the Twelve being the brother of Jesus appears to be a tiny minority view, as the evidence is thin.

[17] The gospels themselves actually give quite differing accounts of the post-resurrection appearances, as explained below.

[18] E.g., Clement (c. 80 CE, Letter to the Corinthians), Hegesippus (c. 180 CE, Ecclesiastical History). Irenaeus (c. 189 CE, Against Heresies) seems to argue that the only legitimate bishoprics were those whose succession could be traced back to the apostles’ appointment; he also seems to be stressing an oral tradition, giving Bishop Polycarp (69-155 CE) as an example of apostolic appointment and faithful tradent of that tradition, with which Tertullian also agreed (Demurrer Against the Heretics, c. 200 CE).

[19] Mark 7:1-13

[20] 2 Thessalonians 2:15; 3:6

[21] Called sola scriptura, one of the popular views of the Protestant Reformation, but a full millennium and a half after Christ. It should be noted that there were other views among Protestants and still are. Calvin and Luther did not totally exclude church tradition. And many Protestants believe in the supplementation of the Holy Spirit in giving the believer understanding.

[22] This is well-known among Greek scholars, and is not merely an anti-fundamentalist argument. See The Synoptic Problem and Statistics, by Andris Abakuks.

[23] Luke 1:2. Not all scholars agree that Luke and Acts were written by the same person, but many do; the writing style is certainly very consistent across the two books. Here we are only concerned with what the authors claim. While there is no claim to authorship for the gospel of Luke, the books of Acts has stylistic similarities and mentions an earlier book about the teachings and actions of Christ, both of which, along with fairly ancient traditions regarding authorship of both books, make it pretty likely that the author of Acts also is claiming the gospel of Luke.

[24] There is actually an excellent argument that Luke placed the revelation at that point in his narrative for literary purposes, and that they may have very well understood that Gentiles were accepted from the very beginning of the movement, based on the Bible’s own testimony, but that discussion can wait till later.

[25] E.g., Luke 2:32; 24:47. The earliest details of the narrative of the birth of Israel are also at odds with their total separation from the nations, even as YHVH-worshippers, a topic to be dealt with later.

[26] I’ll come back to this later.

[27] E.g., Zechariah 14:16-19 says that Gentiles, at some point in the future, will celebrate the Feast of Booths; Isaiah 19 says that the Egyptians will know the Lord at some future day when YHVH will send them a savior, and they will make sacrifices to him, then the Assyrians are mentioned as worshipping with them; those were basically the two large world powers of the day, the kingdoms of the “north and south”. Isaiah 56 is one of the most explicit passages predicting that Gentiles will come to Jerusalem to keep the law. And Isaiah 66 goes so far as to say that some of the nations were even to be taken as priests and Levites; in fact, all nations are said to come to Jerusalem and worship him.