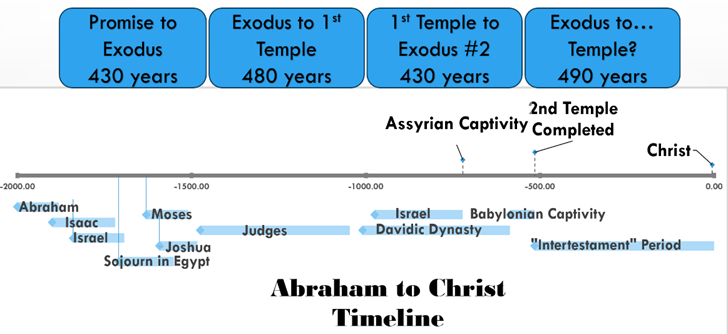

Now that we’ve seen the nature of prophecy over time (see previous article here), let’s examine the full biblical, or at least post-exilic, view of the timeline of prophecy. I do not believe it was an accident that it took four centuries from the time that the promise was given to Abraham till the time of the Exodus, when the promise to make them as innumerable as the stars was said to be fulfilled. I don’t think it coincidence that it was another four plus centuries of bondage and war with saving judges before he finally brought them rest under David’s son Solomon who built God a house, according to the narrative. I do not think it chance that it took them another four centuries to lose that kingdom and again slip back into bondage, after which they were again given another exodus, from Babylon back to Jerusalem.[1] The question remains whether the next and final four-hundred-plus year period that Daniel anticipated before the restoration was to come, which is the one for which we have the most historical evidence, was retrojected back onto Israel’s historical narrative, or whether there was a god of “history as revelation”, orchestrating the previous ones.[2] Fortunately, it is not our purpose to try to answer that here.

In case the diagram was not enough for you to notice, there are certain details repeated here. The second period length is a multiple of twelve; the fourth period is seven times seven times ten, all significant numbers for the Hebrews. But where does the twofold 430 come from?[3] I would be interested to hear from any mathematician any possible details of how 430 was somehow significant. Of course, I have a possible theory, and we already saw it in chapter 1 above. It’s the number you get when you calculate how many years they failed to keep the land Sabbaths before the Babylonian captivity, if you count both the seventh-year land Sabbaths and the 50th. Note that this calculation, based on 2 Chronicles 36:21, reproduces the third time block exactly, the period of the kings. The period of the Davidic rule.

And note one more pattern. God gives a promise at the very beginning of this timeline. And the cycle that’s going to get them there is three-fold: Exodus to Temple, Temple to Exodus, and Exodus to final Temple. Of course, most of the final writing and redaction of the Biblical stories into their current arrangement did not occur until the first part of the final period, after Babylonian exile. So this holy anthology is primarily arranged for those people’s situation. So how did the rest of the world resonate so much with this story?

Herein lies the rub, for anyone who asks, like Pontius Pilate, ‘what is Truth?’ As I’ve noted many times, the Bible is the most influential literary anthology of all time, by far: if anyone wants to seriously take its claims into account, they must direct their attention to the spiritual. The Bible’s prophetic assertions are not merely claims that a talking snake brought evil upon all mankind, or that there’s an invisible man in the sky who will judge us when we die, as George Carlin so crassly put it. The Bible’s story is far deeper, with teachings that would sometimes perhaps make a Zen master scratch his head, and is expressed within a literary tapestry that is the greatest the world has ever seen, which is the subject of a following book in this series. If it’s all a lie, what better things do we have to do anyway? Stargazing or playing with finches on deserted islands, though fun enough, just doesn’t seem near as cathartic. Or maybe I’m wrong.

To see how starkly different the Second Temple period was from the first, check out the rest of this chapter in my book!

[1] Galatians 3:17; 1 Kings 6:1. You may notice that some passages actually say they were in Egyptian bondage for about four centuries (e.g., Genesis 15:13; Acts 7:6); while others say that the time that they lived in Egypt was 430 years (Exodus 12:40). The Bible chronology and genealogies, however, actually fit Galatians 3:17’s take better, that the 430 years were counted from the time that Abraham received the promise. Solomon, according to the narrative, completed the first Temple about 957, and the second Temple was completed about 441 years later about 516. Herod would begin his tremendous construction project which would make the final Temple much more glorious than the first around 20BCE, about 496 years after the initial construction, actually fulfilling Haggai 2:9.

[2] There are many historical details that would seem to point, like the stories of the Bible, to prophetic details. These range from Alexander the Great to the Hasmoneans, and even to Philadelphus II and Antiochus III and IV and Herod. I would very much like to write a book on these because they are fascinating, but I’m afraid that they would not fit in the secular voice that I have cultivated currently for my writing niche. They would make me sound like a Christian apologist. However, just for the fun of it, let’s throw a few in this footnote. Daniel’s 490 years from the time that Babylon was overthrown puts us at 49 BCE, the year Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon, what could arguably be considered as the birth of the Rome of Jesus’ time, possibly tying in with Daniel’s prophecy of the last kingdom under which the Messiah would come (according to some interpretations). Augustus would succeed Julius, but was adoptive son only by law, not by blood, and he would be the first Roman emperor to truly solidify the power of the dictatorship, all without calling himself dictator. Julius would also be the first Roman ruler to be deified, and to be killed at least partly for that reason. Only upon his death would the dictatorship realize full power over the empire, under “son” of the god, ruler of all the Earth. And it would be under this Augustus that Jesus would be born. Scholars have long noted that, although there were many earthly sons of the gods, there were only two who wore the title “Son of God”: Augustus, and Jesus. (E.g., The Son of God in the Roman World, by Michael Peppard) Scholars see this title being given to Jesus as merely competition to the Roman emperor. I plan to argue later in this series that they also intended it as a use of history as couching prophetic meaning. The probable reason that scholars don’t typically entertain this idea is that dramatic irony, as I’ve noted elsewhere, does not happen in real life, at least not with multiple parallels and high statistical specificity. But that does not mean that it cannot be masterfully retrojected.

[3] The number 430 is also found in Ezekiel 4, where he is commanded to lay on his side 390 days, then on his other side for 40, a day for every year; the latter period is symbolic of the time when God will punish them. Similar to the way the 430 years of sojourn in Egypt and the 430 years under the kings would devolve from blessing to curse, we find another example of 430 in Genesis 11:17. After Eber had fathered Peleg, he lived 430 years, and in his days the Earth was divided. Some believers have concluded that this was the separation of the theoretical supercontinent Pangea, after which men were mostly separated until the modern era; however, we need not assume so much to make our point here: in the context of the narrative, the division occurred at Babel. The only point I want to take away is that here, too, we have an example of things going from good to bad within a 430 year period. Our authors are connecting their stories. Nor was Paul the first to see that a law-giver was to come at the end of the 430 years to save the people and set things right (Galatians 3:17).