So far we’ve seen evidence of editing in the Torah, and different perspectives of its various claims. It’s time now to consider where parts of the Torah actually modify previous laws, and even sometimes outright contradict them, and what such differences can perhaps tell us about the authors. Bear in mind that this is not an exhaustive list of differences between laws, but only a sampling.

Your Brother’s Keeper

Exodus 21 says that a Hebrew slave is to be released in the seventh year, without payment. Deuteronomy 15 adds that when you let him go free, you must not let him go empty-handed, but to give provisions; so we see that the Deuteronomy code adds to the law of Exodus, and is more concerned with the welfare of the poor. Another example of this concerns lending to one’s fellow Israelite; while both Exodus 22 and Deuteronomy 15 prohibit the charging of interest, Deuteronomy goes further by requiring a seven-year release from all debts, on the “sabbatical” year. Deuteronomy’s release of slaves may also refer to releasing slaves on this sabbatical year rather than the seventh year of service; the wording seems ambiguous; and again, the sabbatical year is not found in Exodus.

But Deuteronomy does not just seem to alter the Exodus code by adding the requirement of giving Hebrew slaves goods when they go out free. It actually seems to reverse the Exodus 21 rule that allows a female slave to be essentially kept forever, without the seventh-year release. Exodus 21:7, in regard to a man’s daughter whom he sells as a slave, says explicitly “she shall not go out as male slaves do;” in other words, in the seventh year, which had just been detailed for male Hebrew slaves.[1] Deuteronomy 15, on the other hand, explicitly applies the seventh-year release to both male and female Hebrew slaves, directly contradicting Exodus 21.

So far we are seeing these contradictions through our Western eyes. Below, we’ll explore how some of these—but not all—may not have actually be contradictions at all based on ancient conventions of expression.

So what can such differences tell us? Firstly, there is quite a bit of overlap between these laws, so they are not random collections thrown together into one Torah. Secondly, the Deuteronomic school appears to rely on and be a modification on Exodus. What is the difference in the views of the author of Deuteronomy, besides apparently greater concern for the poor? We can tease out at least one more detail regarding motive by comparing one more difference. For Exodus 21, a slave who wishes to forever remain with his master is to be brought “to God”, most likely to one of the places that God would have his priests officiate; recall that Exodus seems to have in view a plurality of places where God would cause his “name to be remembered” (20:24). But for Deuteronomy, which alone emphasizes the centrality of YHVH worship, it would probably be burdensome to have many slave owners bring their slave all the way to the one central place where God would “choose to make his name dwell”,[2] so the owner can simply perform the ceremony of making his slave permanent at the entrance to his own house. Note that this is quite ironically opposite to the places of the sacrifice of the pascal lamb in the two books, as detailed in the previous section.

But wait, there’s more. Unlike Deuteronomy 15, Leviticus 25 is totally different from the Exodus law regarding Hebrew slaves, and only shares a few parallels with Deuteronomy, from which it mostly differs as well. Leviticus 25 seems to outright ban enslavement of fellow Israelites, and requires that a poor Hebrew who has fallen into servitude be treated well, sort of like indentured servants.[3] It says that they shall be with you as a “hired laborer”. Note that this builds on the generosity of Deuteronomy 15, which only says you should give them gifts when they go out. Leviticus 25 also requires that the servant and their families were to be released to return to the property of their inheritance, but not on the 7th year, as in Deuteronomy 15, but on the year of Jubilee, which only came around every 50 years. So the idea of treating your fellow Israelite not as a slave but as a brother is found in both Deuteronomy and Leviticus, but the details of the laws are vastly different; some scholars believe that Leviticus is a later modification of Deuteronomy because of their few parallels.[4] These two passages also share another similarity, in their terminology: unlike Exodus 21, which speaks of a Hebrew “slave/servant”, Deuteronomy 15 and Leviticus 25 speak of your Hebrew “brother/kinsman”.[5]

Again, our purpose is not merely to point out differences and contradictions, but to see what they can tell us about the biblical authors, their beliefs, and maybe even other details about them and when they wrote. We’ve presented some such evidence for the authorship of Deuteronomy, which has some very clear beliefs and worldviews which show through in its teachings. Exodus has less evidence of being a specific “school”. Leviticus, on the other hand, is from quite a different “school” than Deuteronomy, focusing on priestly law, and emphasizing holiness.

Intergenerational Punishment

Another way that we can see differences in the legal systems and their authorial perspectives found throughout the Torah regards who can be punished for a crime. Although the Mosaic law did indeed have many progressive laws for its time, it also had many parallels with the laws of the nations, a few of which were noted in chapter 4. But as we saw in the previous section, we can even see progression within the Torah itself, as its laws were adapted, modified, and sometimes even altered. And perhaps the best example of this regards when and under what circumstances intergenerational punishment was permitted.

In Exodus 34:6-7, we’re told that God visits the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and fourth generations. Yet Deuteronomy 24:16 explicitly says that the fathers shall not be put to death for the sins of the father, and vice versa. I’ve always heard preachers and Sunday school teachers explain this by saying that the consequences of sin fall of the offspring, yet not the guilt of sin. There’s just one problem with this interpretation: it does not match the actual application of the law, with God’s approval, after the timeframe of the Torah, and even within the Torah itself. We’ll consider an example of both. As a side note, many scholars and perhaps Jewish apologists see the Exodus law as a mercy, as spreading the punishment out. I would argue the opposite: that this expression is actually intended to convey the severity of God’s punishment.

2 Samuel 21 is an incredibly interesting story. We’re told that God caused a three-year famine on the land. When David inquired of YHVH, he was told that it was because of blood guilt on the land, which was from Saul killing Gibeonites, to whom the children of Israel had sworn an oath not to kill, despite God’s command.[6] The idea that the entire nation can be punished for the sins of individuals is another facet of this discussion, but for now we will only focus on the sons being punished for the sins of their father. First, note that the people as a whole are being punished for the sins of a man who is dead. And more specifically, David killed Saul’s sons. God then relented and again sent rain to water the crops. In other words, God approved of the execution of Saul’s sons for the sins of their father. Interestingly too, it was the Gibeonites who actually named the punishment, not explicit revelation from God.

The nation of Judah is also said to be punished for the sins of Manasseh, long after his death, and even after the reforms of Josiah, who served YHVH like no king before; in fact, he is perhaps presented as the quintessential son of David who finally ushered in a period of pure YHVH worship. This seems very odd, then, for punishment for the sins of Manasseh to be withheld until the nation was actually serving God.

But perhaps one of the most curious stories of intergenerational punishment is with Ahab, who is presented as perhaps the epitome of an evil king who rejects YHVH, for there was “none who sold himself to do evil in the sight of YHVH like Ahab.”[7] Elijah confronts Ahab in the very vineyard for which he has just murdered a man, and told him that his entire household would be destroyed for his sin. When Ahab tears his clothes and puts on sackcloth in mourning and, ostensibly, repentance, God relents a little, and says that he will not bring the disaster in his days, but in the days of his son. I’ll rephrase in case you missed it: God is not going to punish Ahab for his sins because he repented; instead, God will punish his son for Ahab’s sins.

Now let’s go back to the Torah. We’ve already seen how different voices are found across the laws of the Torah, particularly in Deuteronomy. We’ve noted that God visits the iniquity of the fathers on the children in Exodus. Numbers also agrees.[8] Did God, in the Torah, approve of executing children for the sins of their fathers, as David did to the sons of Saul? Because, if so, I don’t believe the argument holds up that says Exodus is in harmony with Deuteronomy because it is not speaking of guilt, only consequences.[9] To understand the differing views of these laws, we now turn to two stories in the timeframe of the Torah.

The first account is one we’ve already seen, the punishment of Dathan and Abiram in Numbers 16. But if you read the account carefully, you see that it’s not just they who are punished. Moses told the congregation to get away from those men’s tents. The men came out to the entrance of their tents. With who? With “their wives, their sons, and their little ones”! When God caused the earth to swallow them, he also executed the families for the fathers’ sins, including their little children.

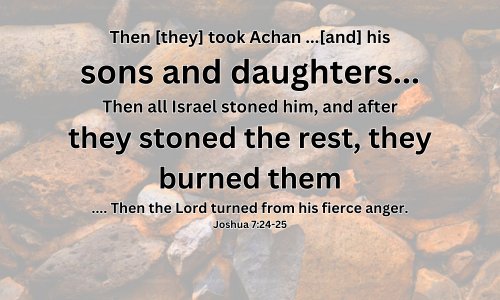

The second account is most like the story of David killing Saul’s sons for Saul’s sins, because it is not God’s hand that does the killing, but the people’s. It is the account of Achan, which actually falls just outside the Torah, in Joshua 7. Recall that God has already let people be killed in battle because of Achan’s sin of touching the plunder, which was supposed to be devoted to destruction. But when they go to punish Achan according to direct revelation from YHVH, there are a few details that I imagine most Sunday school classes don’t notice. In order to purge the sin from Israel, they must not only devote Achan to destruction, but also the plunder he took, his livestock, his tent, and everything in it. Including his sons and his daughters. And they burned them with fire and stoned them with stones. Lovely story.

We’ve already noted how Deuteronomy appeared to be a later perspective in the way that it modified the Exodus laws regarding slavery, and in its being the only law in the Torah regarding centralized worship, and not being practiced by the kings of Israel for hundreds of years. So too, Deuteronomy also takes what is perhaps a more “modern” view of justice, where the children are not punished for the father’s crimes. We see the view of Exodus in the story of David killing Saul’s sons; the first time we see the Deuteronomic view appear is in 2 Kings 14, where Amaziah does not execute sons of the men who killed his father, according to “the Book of the Law of Moses”. He ruled in the first half of the 8th century BCE, a couple of hundred years after David.

We see Psalm 103:8-10 reference the passage in Exodus 34:6-7, yet it seems to modify it at the end. The Lord is compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness. Yet here, the Psalm departs from Exodus. Instead of extending his punishment of the guilty for generations as in Exodus, the Psalm says that he will not always accuse nor extend his anger forever. A similar revising restatement of Exodus 34 actually appears in Deuteronomy itself, in 7:9-10.

Useful Observations

The list of differences in the Torah’s perspectives could go on and on. For instance, why is there a passage that says that God did not make himself known by the name YHVH before, when earlier accounts clearly show that he did?[10] Why does Exodus 33 appear to be oblivious to the fact that the Tabernacle has not yet been built? Was there a “temporary” tent of meeting before the new Tent of Meeting was built? And why was it pitched outside the camp, if they were commanded to pitch the Tent of Meeting in the center of the camp in Number 2? And try to nail down the age that a Levite had to be in order to serve the Tabernacle: Numbers 4 places the minimum at 30 years old, and states it a significant seven times;438 but chapter 8 says the age is 25;[11] David would later change it to yet another age: 20 years old.[12] But there’s no need to keep citing these.

We’ve seen enough differences within the Torah, some of them outright contradictions. We should pause at this point, perhaps as the fundamentalists attempt to catch their breath, or their faith, and make some useful observations.

We’ve seen that the Torah actually contains collections of laws, not one unified legal system. These collections often overlap and agree, but often they will modify one another, and sometimes even outright contradict each other. We can even see that some came later, by the way that they modify earlier ones. These are excellent opportunities for improving our understanding of when certain laws were actually in place, and how the legal system of Israel evolved over time. But there is perhaps a more valuable and fascinating observation that we can now make.

It’s been argued that certain men in power, such as Ezra, were responsible for pushing through certain texts as authoritative. To a certain extent, this is not inconsistent with the Bible’s own testimony, especially regarding Moses. In the chapter on textual criticism, we saw how the ancients did not seem to have the same attitudes toward sacred texts, and would sometimes openly modify them, even attaching obvious additions to the ends of older texts. However, the irony of this is that they would quite often leave the earlier texts untouched, and simply add more material which modified or even contradicted the previous texts. They even treated the earlier texts as sacred, without trying to argue with them, even while contradicting them.[13] This seems a paradox to the modern mind, but that’s exactly what they did. So in a sense, fundamentalists apologists are actually right: the texts have quite often been preserved! Just not in the way preferred by those who hold a dropped-from-the-sky-complete view of inspired books.

At this point, you may have noticed that we’ve answered very few questions regarding when, why, and how the Torah actually developed. We mainly focused on simple evidence that it in fact did develop. This is because I’m saving several facets of biblical origins for later books. For now our only focus has been to train our eye to begin to see such evidence. We must first understand the nature of the texts before we can try to tease out when, how, and why they came to be. And frankly, there is much that we simply cannot know, contrary to the certainty with which modern source critics will make many claims. To read the next section on how we impose modern views of law on the texts, creating meanings and contradictions that the original authors would never have intended, check out the next section in my book here.

[1] There are of course circumstances listed under which the female slave could be released, but they have nothing to do with the seventh-year release.

[2] Deuteronomy 14:23

[3] I believe that servitude is a hard institution for many moderns to grasp, who tend to view it merely as a sign of immorality and illiberal, backward people who simply hadn’t achieved the enlightenment of moderns. However, in the case of a fellow Hebrew, there was no bankruptcy court where debts could simply be waived away with the swipe of the judicial pen, and there were very few social safety nets. (The right to glean is one of the few, but it was less welfare than “workfare”.) In the case of a foreigner taken in battle, servitude was probably usually preferable to the alternative: death. To simply pigeonhole the ancients as “evil” because of their institutions of servitude is to ignore the reality of war and poverty before the comforts and weapons of mass destructions (i.e., sometimes deterrents) of the modern era. And even moderns have not abolished involuntary servitude, despite the universal canard to the contrary, even in the most developed nations. Simply read very carefully the wording of the 13th amendment of the US constitution, and you’ll see the exception, which now affects the highest percentage of prisoners the world has ever known. Land of the free indeed.

[4] “The Hebrew Slave: Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy”, by Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber, thetorah.com. Other scholars argue that the Leviticus law actually came before Deuteronomy (e.g., Debt-Slavery in Israel and the Ancient Near East, by Gregory C. Chirichigno, Jsot Supplement Series, p. 329).

[5] Compare Strong’s 5650 and 251

[6] See Joshua 9 for that story. Note too a different way the ancients had of looking at the world. When there is some national hardship today, people do not consult God to see what sin it is for.

[7] 1 Kings 21

[8] 14:18

[9] This seems like special pleading anyway. If the government sentences you to prison time for a crime you didn’t commit, you would find no comfort if they told you that they hadn’t actually found you guilty. Rather, they were only meting out the consequences of committing the crime. I believe the term for this is “injustice”. But I could be wrong….

[10] Compare Exodus 6:2 to Genesis 15:2-7; 18:14; 22:14. Perhaps these passages could be explained by later paraphrasing of what was actually said; however, Moses’ mother’s name (Ex. 2:1-10; 6:20) would not have been such a paraphrase. “Jochebed” means “YHVH is glory”.

[11] Some scholars have suggested that the content of chapters 7-9 appear to have enough differences from the first 6 chapters of Numbers that they were added by a redactor from a different priestly school.

[12] I Chronicles 23:24-27

[13] See below.